Next year the BSI will publish the world’s first Circular Economy Standards and the government has already indicated that it will announce new recycling targets to 2020 for paper, aluminium, steel and wood packaging. So has the time come for you to act rather than just talk?

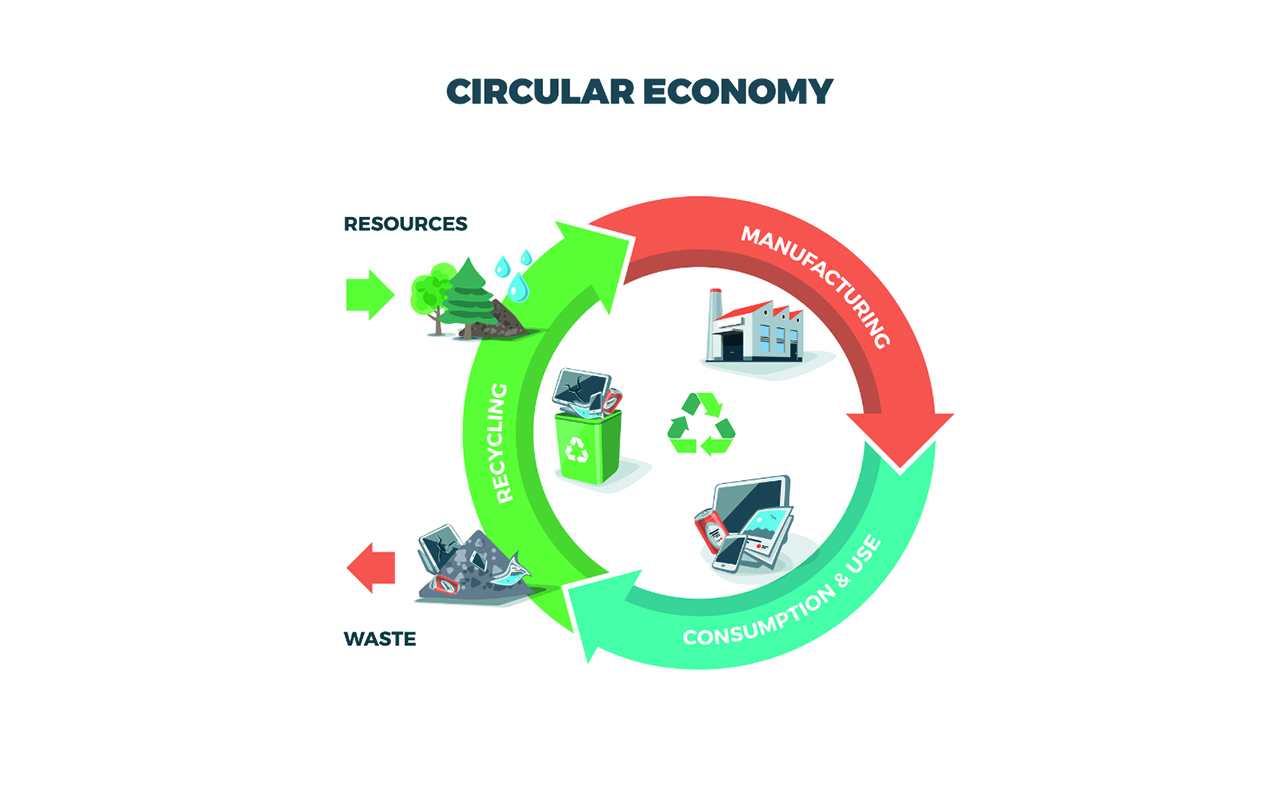

In an age when the planet’s resources seemed almost infinite, in a time when only a few scientific geeks had even heard of a theory called global warming, the linear economy - in which materials are grown or extracted, turned into goods and then disposed of - served companies reasonably well. The flaw in this model - which has become increasingly serious as each passing year is dubbed “the hottest since records began” - is that economic growth relies on material consumption. Looking forward, we have two choices: accept that that the economy will not only fail to grow but actually shrink or change that model.

The first option is socially and politically untenable - the middle class, which is expanding globally, will not stand for it - so we must do what we can with the second and replace the linear economy with a circular one. What does this mean? Ideally, a circular economy is one in which we keep resources in use for as long as possible, extract the maximum value from then while in use, then recover and regenerate products and materials at the end of their service life.

The concept of the circular economy has been around for years but Britain’s print service providers are about to hear a lot more about it. Next year the British Standards Institute will publish the world’s first Circular Economy Standards and, in next year’s spring budget, the government has already indicated that it will announce new recycling targets to 2020 for paper, aluminium, steel and wood packaging. The EU is also proposing to raise recycling targets to 70% by 2030 and - even if Brexit has been accomplished - such measures will set standards British businesses exporting to Europe will be expected to meet.

The British government feels compelled to act because there are signs that the process of creating a sustainable economy is losing momentum. Household recycling rates have effectively been stuck at the same level since 2013 and, in 2016, fell from 44.7% to 43.9% - a decline that looks small but is the first drop since the Department for the Environment and Rural Affairs began keeping records. Explanations for this drop vary - some councils say they have had to slash spending on waste management - but everyone involved in the recycling system admits that it has serious flaws.

A circular economy can mean many things, and that complexity is one reason why the BSI consulted so extensively in preparing its new draft standards. For PSPs it will, at the very minimum, increase the pressure to consume less and recycle more. It may also stimulate the quest for environmentally friendlier options across the production process - from raw materials to inks to printers. For example, if a client asked - as Ikea is now doing of its suppliers - ‘can you convert waste into raw material for us?’ what would you say?

The difficulty here is that, as the 2017 Widthwise survey showed, many buyers of wide-format print don’t even ask about their supplier’s environmental credentials. This lack of concern does not, despite the escalation in rhetoric about the issue, seem to have changed much in the last few years.

Suppliers can play their part too. This summer, Motorola revealed that it had filed a patent for a self-healing mobile phone display. The design includes a “shape memory polymer” which, the patent application says, could reverse, at least partly, any damage. In theory, a user could press a ‘repair’ button and the damaged phone screen could mend itself. Other companies and researchers are looking to develop self-healing for other applications, include polymers, concrete and rubber. With AI, wide-format printers could extend their useful life by self-diagnosing.

There are two obvious problems with these scenarios. The first is us - we are so primed to prize novelty that many of us regard having an old mobile phone as a social disgrace akin to body odour. The second is the companies that sell us stuff - whose business model is based on their ability to sell a specific number of new products, whether they are mobile phones or digital printers. There is a way to manage the second challenge. Companies need to move to a service model, as Rolls Royce has done, by charging airlines for the amount of time its engines are used.

The first challenge may be harder to deal with. Many of us are hard-wired to crave the newest, fastest, and most expensive - whether it is a printer or a car. What is needed, as Dejan Sudjic, director of the Design Museum, argues, is a new kind of consumerism that priorities longevity over novelty. This may never apply to areas where technology is changing fast but it could change the way business buys office furniture, stationery and raw materials.

What the circular economy isn’t, is a magical fix for global warming. It is part of the answer but only that. The bigger revolution to come - in which, like John Lennon, we imagine no - or a limited number of - possessions is still decades away.