Textile printing has inkjet printer manufacturers excited, but how’s the technology squaring up to the demands of sign and display printers? Nessan Cleary investigates.

A great deal has been written about the potential opportunities for profit from digitally printing images to textiles. Most of this is meaningless to anyone working in the display graphics business because the figures deliberately conflate the garments and home furnishings markets together with signage and confuse different geographic areas.

Thus the UK market is a drop in the ocean compared with, say, China, but the opportunities are completely different.

Equally, the garments market is likely to account for the bulk of textile printing, followed by home furnishings with signage making up a smaller percentage.

As Stephen Woodall, Hybrid Services’ national sales manager for textiles, points out: “You have to understand more about the printing as well as the sewing and finishing equipment so it’s quite a considerable step to move from signage to fashion.” And of course it’s also about understanding a totally different marketplace and seeing value in investing the time in energy in doing all it takes to make that kind of jump.

But lets not ignore the fact that there is an easier route to what can be a lucrative market printing display graphics to textiles, mainly for POS (including lightboxes, as well as exhibition graphics plus banners, flags and backdrops) where there are now well documented good reasons for switching from vinyl to fabric. And, of course, there is always the tantalising possibility of then expanding into other areas such as décor and corporate wear.

Dye-sublimation or not?

When it comes to looking at textile print technology you could, of course, start by using a standard wide-format machine. Indeed, HP has gone out of its way to position its latex printers for textiles, with some models, such as the Latex 370, having a platen specifically for textile printing. Equally, UV printers are widely used for textile applications and there are a number of substrates that will accept solvent inks.

There are advantages to investing in a dedicated textile printer but it’s really a question of volume - if you have enough work then it probably makes more sense for that machine to be a dye-sub printer.

There are two main advantages in using a dye-sub printer: there’s a far wider choice of substrates available; and dye-sublimation produces much brighter, more vivid colours.

Different fabrics

There’s no one-size-fits-all approach to textile printing because ‘textile’ is itself a word that covers several different materials, from cotton and silk through to wool, all of which require different types of inks - and some also need extensive washing and drying.

But for the purposes of display graphics we’ll look at polyester-based substrates, albeit that these are blended with other materials for specific properties such as a softer feel or better durability. These can be used with water-based inks and a dye-sublimation process, whereby the printed textile is subjected to considerable heat to drive the ink into the fabric. This sublimation process leads to very bright colours, with excellent resistance to cracking, abrasion and washing. But crucially it also means that the ink is no longer sitting on the surface so that the textile retains its own feel or handle.

There are two basic approaches - printing direct to the textile, or printing to a transfer paper, and then sublimating the image to the textile through a heat press or calendar. There are good arguments for the use of each. Some vendors claim that using a transfer paper allows for brighter colours. The transfer method also means that you need little or no coating on the textile, so that it has a better feel and costs less. Also, using a separate calendar can allow for higher volume, if only because it can handle the output from several printers.

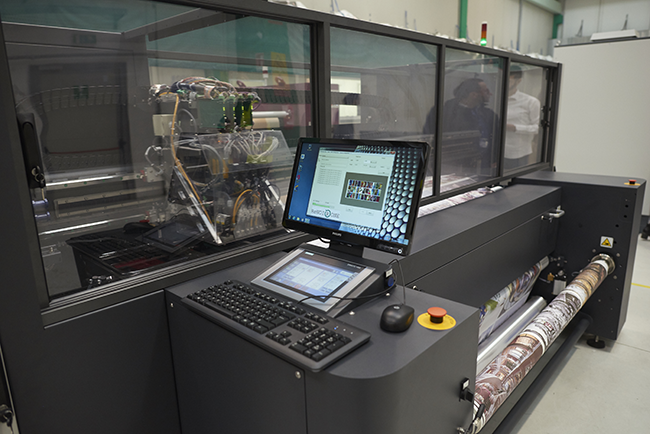

The alternative is printing direct to the fabric and using a built-in fixation unit, which is becoming more popular thanks to improvements in direct disperse dye-sublimation inks, particularly with the use of pigment inks. In theory, this can be more efficient because the printing and fixation are all done in a single process. These machines are more expensive, but you won’t need to buy a separate calendar.

This method requires coated textiles, which does make the textile slightly more expensive. But, of course, you save on not needing the transfer paper for printing or the protective paper for a calendar. Also the calendars can take an hour to heat up and it can be expensive to maintain that temperature.

Stewart Bell, managing director of Mtex UK, says: “It’s still a bit of a challenge to print to textile because every single textile has a different property to it in terms of stretch and the coating so there’s still a learning curve but we have simplified it as much as possible.” Thus in recent years we have seen a number of improvements, mainly in terms of new substrates as well as better inks that deliver brighter colours. In addition, most textile printers now also include a sticky belt to counter the tendency of the fabrics to stretch, thus making it easier to print a higher quality image at faster speeds.

However, textile printing is still not the easiest area to get into it. There is a high initial investment because of the need to sublimate the prints, and a steep learning curve in the handling characteristics of the various substrates. But this in itself may be an advantage as it thins out the competition and allows for higher margins per job.